Whatever their specific hopes, fears, regrets and sighs of relief about what finally made it into the text of the Kunming-Montreal Agreement, which was adopted by governments at COP 15 in December, stakeholders across public, private and civil society sectors agreed that the new Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) represents an historic achievement that sets us on a path to halt and reverse nature loss by 2030.

This article outlines some of the key features of the GBF that can help a business audience to grasp the significance of the agreement for the evolving policy, standard-setting and investment landscape, and ultimately how this is going to translate in many global jurisdictions into mandatory requirements for nature-related financial disclosures.

Buckle up as we also take a whirlwind tour of some of the fast-emerging new standards and frameworks in this space and the coalitions and networks that are accelerating the work to prototype and pilot them. What’s useful to bear in mind here is that the train tracks for this new adventure have to a large extent already been laid, in part due to the extraordinary momentum and sense of urgency around the need to address climate change, but also due to what might be best described as ‘quantum thinking’. By this I mean an ‘alchemistic’ mindset adopting a systemic, integrated approach that seeks out interconnections, synergies and economies of scale that result not in incremental, linear steps forward but in a quantum leap that catalyzes the emergence of something greater than the sum of its parts.

The Global Biodiversity Framework

One of the most striking features of the agreement, which was negotiated and agreed to by 196 states and the European Union at the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity’s COP15, is its breadth and inclusiveness.

As the Capitals Coalition points out, the framework seeks to harness the contributions of all stakeholders across society and the economy to reverse nature loss, placing business accountability at the heart of the endeavour. The GBF also explicitly refers to the rights and critical contributions of non-state actors such as indigenous peoples, local communities, and youth and women’s groups, who must play a key role in the creation of the national biodiversity strategies and actions plans that will drive implementation of the framework.

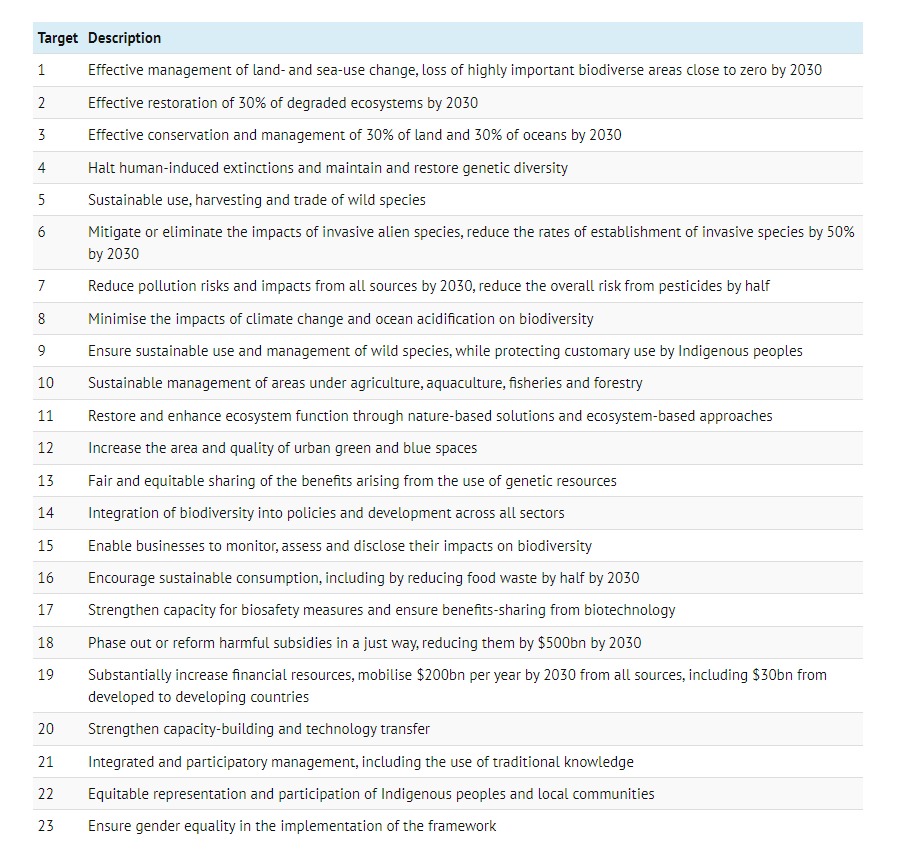

The overarching aim of the GBF is for people “to live in harmony with nature” by 2050. To achieve this, the GBF has set out a “mission” to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030. Consisting of 23 targets, the Framework essentially constitutes a roadmap for nations to conserve 30% of the world’s land and 30% of the ocean by 2030, to halt species extinctions, reduce the impact of pollution, redirect environmentally harmful subsidies, mandate assessment and disclosure on nature for businesses and ensure that the benefits received from nature are equitably shared.

Target 15 is the keystone of the Framework from the perspective of business accountability. In a nutshell, countries who have signed the agreement have committed:

“to ensure that large and transnational companies and financial institutions regularly monitor, assess and transparently disclose their risks, dependencies and impacts on biodiversity […] along their operations, supply and value chains and portfolios […] in order to progressively reduce negative impacts on biodiversity, increase positive impacts, reduce biodiversity-related risks to business and financial institutions, and promote actions to ensure sustainable patterns of production.”

In practice, it is expected (and intended) that these countries will legislate to make the relevant disclosures mandatory for companies in these two categories. And just as TCFD (the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures) has provided the framework to facilitate the adoption of new climate legislation, so we can expect TNFD (the Task Force on Nature-related Financial Disclosures) to accelerate the pace of mandatory and voluntary disclosures relating to nature and biodiversity. More on this below.

Like the Paris Agreement on Climate, the Global Biodiversity Framework and its underlying documents are not legally binding. They are therefore expected to follow a similar process whereby nation states who have signed the agreement – the only UN member state not to have ratified the treaty is the United States, although it still has a presence at biodiversity COPs – will submit national targets and action plans, specify a date for review of progress and then ratchet up their ambitions following their stocktaking.

As many participants and observers of the COP15 process have pointed out, the challenge will be in turning pledges to action and the devil will be in the details of the action plans themselves as well as the governance and monitoring mechanisms, many of which are still to be defined.

Financial and Business-related Aspects Of The GBF

Not surprisingly, the contentious matter of how to finance implementation of the framework was at the heart of intense discussions in Montreal. There will be significant financial implications for countries, notably those in the global south – where biodiversity is concentrated – who are largely responsible for implementing the GBF. The current biodiversity finance gap is estimated at roughly $700 billion per year over the decade. The GBF hopes to mobilize “at least $200bn per year” by 2030 from “all sources” – domestic, international, public and private. This money will flow into a special trust fund, the Global Biodiversity Framework Fund, which will have its own “equitable governing body” dedicated to achieving the goals of the GBF.

The strong presence of representatives from the global business and financial community at COP15 – and their strong advocacy in favour of the GBF – coupled with the increasing attention of central banks and financial regulators on the risks of nature and biodiversity loss to global economic resilience and financial stability are clear signals of the trajectory we are on. Moving forward, companies can expect investors to place much greater emphasis on material issues relating to nature and biodiversity, putting them on a par with climate-related issues and seeking to tease out the interconnections between them. This trend is likely to accelerate considerably later this year when version 1.0 of the TNFD framework will be released (the beta framework is already on its third iteration).

Another piece of the GBF that is likely to change the policy and business landscape in a significant way is Target 18, which includes the goals to:

“Identify by 2025 and eliminate, phase out or reform incentives, including subsidies, harmful for biodiversity […] while substantially and progressively reducing them by at least $500 billion USD per year by 2030, starting with the most harmful incentives, and scale up positive incentives for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity.”

As Carbon Brief have pointed out in their comprehensive summary of the outcome of the COP 15 process and content of the GBF (well worth a read), analysis published in February 2022 found that governments around the world spend at least $1.8tn each year on subsidies that exacerbate biodiversity loss and climate change, a figure that is equivalent to 2% of global GDP. The intention to reroute environmentally harmful subsidies and transform them into environmentally beneficial ones is a good example of quantum thinking, whereby a holistic view of the whole interconnected context reveals opportunities that were hidden when viewed from a fragmented, siloed perspective.

Clearly, it will take some time for the expected impact of the Global Biodiversity Framework to trickle down and kick in, and changes in the business, investment and wider societal landscape will no doubt be felt sooner and more concretely in some jurisdictions than in others. However, as the next section of this article seeks to illustrate, there is a strong likelihood that change will come faster than many expect, accelerated by network effects and multi-stakeholder collaboration.

Game-changing Collaboration In Service To An Integrated Capitals Approach

The most suitable metaphor that comes to mind to convey the surprisingly extensive and effective network of stakeholders that are collaborating to drive systemic change towards a sustainable, inclusive economy is that of the mycelium. Sometimes referred to as the ‘wood wide web’, mycelium is the massive underground web of fungal threads that connect, sustain and regenerate forests and natural ecosystems.

At the heart of the mycelium-like web of collaborations ongoing in this space is The Capitals Coalition, a multi-stakeholder initiative involving over 400 organizations across seven broad stakeholder categories:

- Business

- Finance

- Government

- Science

- Accounting & Standards

- Civil Society

- Multi-stakeholder Groups

Its ambition is “that by 2030 the majority of businesses, financial institutions and governments will include the value of natural capital, social capital and human capital in their decision-making and that this will deliver a fairer, just and more sustainable world”.

The Coalition works to ensure that different parts of the system are connected to one another so that its extended network of many thousands of global partners can together “accelerate momentum, leverage success, connect powerful and engaged communities and identify the areas, projects and partnerships where we can collaboratively drive transformational change”.

Not surprisingly, the Capitals Coalition was one of the key contributors to the COP 15 process and has for years been convening and collaborating its way towards a highly ambitious set of targets and outcomes on nature and biodiversity within the wider context of an integrated approach to all capitals (natural, human, social, produced). On this subject, keep an eye out this year for early iterations of an integrated Capitals Protocol, which is under development and seeks to bring together the existing Natural Capital Protocol and Social & Human Capital Protocols into a single framework document. You can read more about this work here.

As part of its work, the Coalition has partnered with other leading organizations to provide a high-level set of actions – Assess, Commit, Transform, Disclose – called ACT-D, which companies wishing to prepare for their future response to the Global Biodiversity Framework can refer to for step-by-step guidance and resources. ACT-D builds on existing action frameworks and guidance including:

- Natural Capital Protocol

- Science Based Targets for Nature Initial Guidance for Business

- World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) building blocks for what nature positive means to business

- BfN Steps to becoming nature positive

- Task Force for Nature Related Disclosures Beta Framework

If you do happen to lift up this rock and take a quick glance at these mycelium-like networks, I’m guessing that you too will need to pause for a moment to take in the significance of the momentum that is already underway in this field and its future implications for business actors.

How the TNFD Framework is Shaping Up

A closer look at beta version 3.0 of the TNFD framework reveals a very thoughtful, integrated approach that has been collaboratively designed with the kind of quantum thinking that is fast becoming a hallmark of the actors in this space. Here are a few examples to give a taste of how companies will need to equip themselves with a holistic mindset:

- TNFD builds on the same basic structure as TCFD – Governance, Strategy, Risk & Impact Management, Metrics & Targets. Some adaptations have been made and some new elements added to align with the subject of nature and biodiversity, including under Metrics & Targets D: Describe how targets on nature and climate are aligned and contribute to each other, and any trade-offs. (See pp.14-15).

- In addition to the assessment and disclosure of nature-related risks and opportunities, companies will need to assess, manage and disclose their dependencies and impacts on nature. This adds an entirely new dimension (inside-out) when compared to TCFD, which focuses on climate-related risks and opportunities for the company (outside in).

- There is strong emphasis throughout the draft framework on the need for companies to develop an integrated understanding of their risks, opportunities, impacts and dependencies spanning the dimensions of Climate & Nature, but also the connections between Environment & Social issues and impacts.

- The aspiration for an integrated approach is also articulated in terms of the targets and transition plans that companies will eventually be expected to disclose.

Companies already grappling with the consequences of existing and imminent disclosure frameworks may feel anxiety levels rise as they discover and explore these new panoramic views of what is on the horizon. While the next leg of the journey might look like a steep climb, it is reassuring to know that there is a wealth of guidance, support and examples available to help companies build their fitness, prepare their internal processes, and cultivate the collaborative skills and integrated mindset necessary to cross the threshold to this next level. We can also take comfort in knowing that it’s not necessarily the quantity of work that makes the difference, but the quality of the perspective we bring with us along the way.